Q&A with: Nick Compton, England cricketer turned photographer

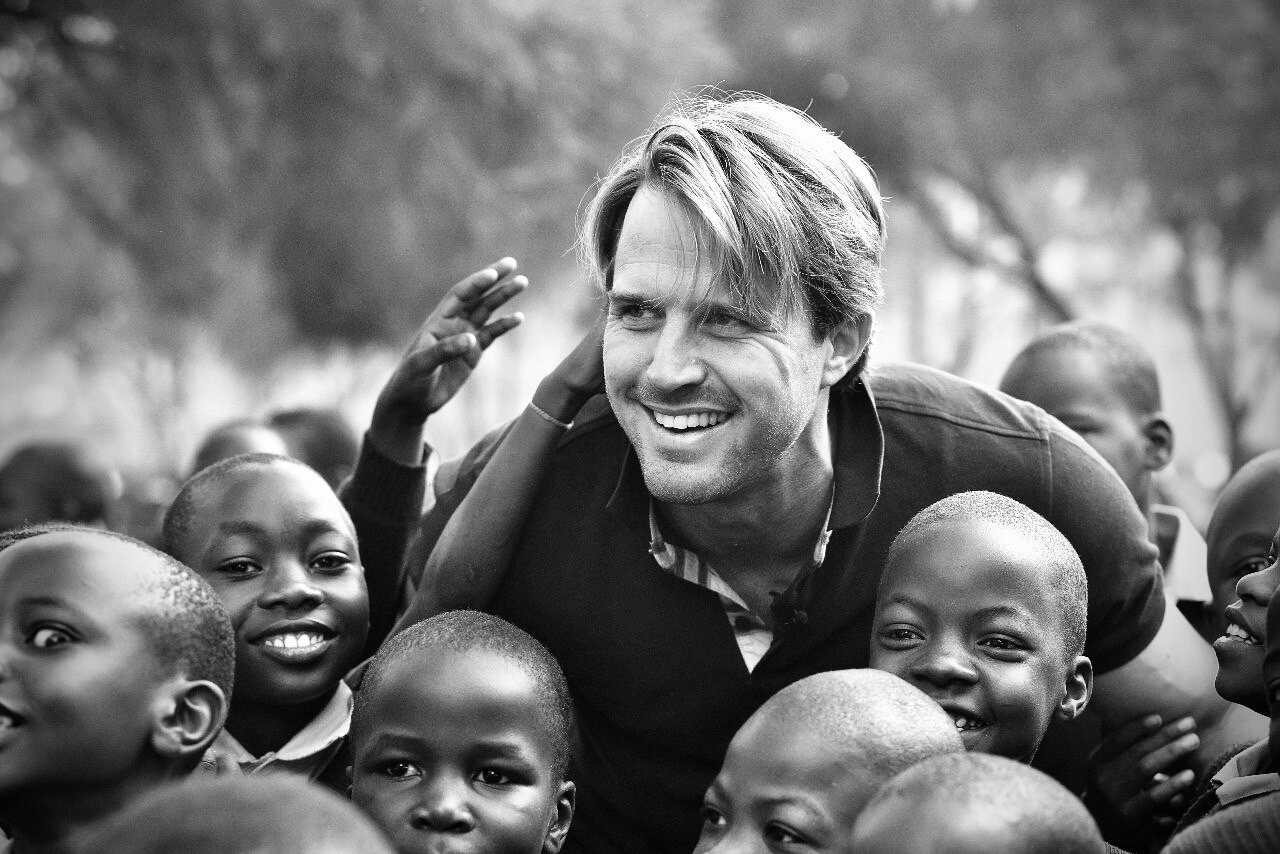

Nick Compton is perhaps best known for playing test cricket for England but, having retired from the sport in his mid 30’s, now pursues a life as a fine art photographer. Over the last few years he has visited Alaska, Uganda, India, South Africa and numerous other locations to work on his print collections, often returning with stunning results. Here he tells me more about his journey from elite sportsman to photographer.

Your ‘first’ career was that of a professional cricketer, playing test cricket for England before retiring in your late 30’s. You’re now focussing on your ‘second’ career as a photographer, stating you’re happier with a camera in hand than a cricket bat. Is this a new development or had you planned for a future in photography even while playing cricket?

My cricket career came to an end slightly prematurely; I had always had ambitions of captaining and fulfilling a leadership position after my England career, with my county Middlesex, as I wanted to help develop and mentor the next generation of cricketers. Sadly at the time there was no position available and I’d also had a long history with injuries which, over a long period of time, does take its toll.

In terms of photography then I think yes, I perhaps am happier with my camera in hand, it’s a conduit to a life less intense. When I was playing professional sport you’re constantly in the public eye, constantly under pressure, but contrast that to taking a camera out to Kenya or Alaska or walking through a city in India, you lose yourself. You don’t have that performance pressure and can let your creative instincts guide you and lead you in to places where your imagination take control.

For me photography has perhaps always filled two voids; one I love art and photography as a skill, I’m very visual and like taking photos and being creative, but it was also a chance to escape the pressures of international sport. There’s no doubt, when you look at mental health, which is such a prevalent topic at the moment, being mindful, being creative, using the other side of your brain is so therapeutic and increasingly important.

You were on the famous tour of India in 2012 when England won a test series there for the first time in almost 30 years. You had your camera with you and as a player would have had access to and witnessed some special events not many others got to see, was this something you made an active effort to photograph?

I think this was one of the most incredible experience I’ve had, winning a test series in India is a dream for any cricketer not just an England cricketer.

It was a hugely visual experience; India’s a country where cricket is almost seen as a religion, so having the opportunity to get out at sunrise where people start playing cricket in the street at 6.30am, and you have the dust that comes up mixing with the colours, the textures and the sun rise, it’s something to be experienced. Who wants to just sit in a five star hotel, which you can do anywhere in the world?

I might never play cricket in India again and so taking the camera out on a few days off, wasn’t something I had planned, but having it there with me and knowing a few photographers on tour made it a no brainer. Walking those streets with my camera is probably one of the better experiences I had on that trip, apart from hitting the winning runs…

As you now transition in to pursuing photography full time, do you find there are traits you developed playing sport at an elite level that help? Is there a relentless pursuit of perfection or a desire to be the best at something that you find helps in an increasingly competitive photography industry?

There are no doubt some transferable skills. I think the individual pursuit of excellence is a brilliant example. Having a camera in hand is just like having a bat, it’s about the expression of your talent and that comes from the photo you see, not the one anyone else sees. It’s how you visualise it, how you photograph it and what position you get in to, there’s a daring individuality to it as well as an expression of your character, and sport is no different.

If we strip it back to a skill level, taking that amazing photograph is the same as scoring a fifty or hitting a couple of cover drives. There’s that real adrenaline or endorphin rush which is why I enjoy photography so much because again it comes back to the individual expression of yourself and your talent and your eye. I believe you can only get better and that stems from your passion for it.

You grew up in South Africa, not moving to the U.K until you were in your teens, do you find this sculpts where your passions lie now with wildlife photography? Are your future plans routed in Africa as well?

My upbringing in South Africa was hugely influential. I had a Dad who was a wildlife TV presenter and so spent a lot of time in the northern part of the country, Kruger National Park and many other parks or reserves, and was very lucky to have the upbringing I did there - it’s a wonderfully diverse country and so culturally rich.

There’s no doubt that getting out in to the wilder parts of Africa and spending time with wildlife is an incredibly rich experience, there’s few better things to do or more enjoyable ways to lose yourself.

Are my future plans rooted in Africa? I mean look I’d like to spend a lot of time there, when you’re from Africa you can never get rid of that, its always in you. My family still live there and I spend a lot of time back home, it’s probably where I feel the most free and connect with most. I feel safe and comfortable back there so there’s no doubt my childhood there has had a massive impact on the way I see things and what I’m passionate about.

This year you ran a successful campaign with Contribute.To, allowing you to fund a project in South Africa documenting life in areas society ‘forgets’, focussing particularly on the affects of Covid in areas with such little support. What made you want to take on this project and what has the response to the images been?

I think Covid and the various things we’ve endured that come with it, societal changes, alterations to habits and locations as well as how and where we live have made a big impact on how we see things. It’s had a big impact on what I’ve done, I went back to South Africa to spend time with family, and the silver lining was that I hadn’t spend time with them like that since I was fifteen, when I came over to the U.K as a school boy, so it was great to have that time again.

However, it also made me aware of what other people were going through and how societies were having to adapt, especially in more rural, developing countries.

In South Africa, Cape Town has always been a home from home and place I love to go to. I’m always looking for images and regularly drive past Khayelitsha community (Xhosa for ‘New Home’), built on the sand dunes outside of the city. I began to notice more and more houses being added to the sand dunes and thought it was immensely visual, particularly in the evening light that Africa is so famous for. The contrast between the sand dunes and these elaborate, colourful homes that people had had to erect during covid because they had lost their jobs and couldn’t afford the rates where they had been living was striking.

A lot of families had been ripped up and had to be moved out, and I found it humbling immersing myself in these communities, meeting these people, hearing their stories and from a photographic point of view I just thought it was something different.

The experience really touched me, I’ve always had a great affinity for South African people, as my Dad did as well, so getting to have that time to speak to them was intriguing.

I was chuffed with how the Contribute.To fund went and how many people supported me so we could tell the story to a wider audience, something I feel is of great importance right now.

You’ve turned your attentions to wildlife photography recently, with a trip to Uganda photographing gorillas. The Bwindi Impenetrable Forest is regarded as one of the toughest photography destinations as the forest is thick and dark, how did you find the experience?

Being an innate traveler and photographer searching for gorilla is one of the most exciting wildlife experience I’ve had.

The Bwindi Impenetrable Forest is everything people says it is. For a start it’s pretty dark and that makes it a very tough place to photograph. One of the main reasons for that is that you’re in thick forest, while the gorillas are dark too, with such small eyes set in a large head so it’s tough to get a well focussed shot. You have to wait for the conditions to be right and the camera settings have to be spot on in such dim lighting conditions. With wildlife photography you often don’t have much time to get the shot or get in position, so you might only get one click at it, if it’s not sharp you’ve missed the opportunity.

I think that for me presented a huge challenge and I could just feel my sporting competitiveness come up as I didn’t want to miss that shot, if I did I got down on myself. It’s also physically demanding, hiking through the forest which is not an easy place to hike but my word when you do see the gorillas it really is mind blowing. They’re incredible animals and being up close and personal with them is an experience I loved. When you are toe to toe with a wild animal its an exhilarating experience that’s hard to match.

As well as this you photographed brown bears in Alaska a few years ago, an experience you did on foot - how did you find being so close to the wildlife and on their terms?

Being on foot is so different to being in a car or being driven. You do feel vulnerable, you feel exposed, but there’s something empowering about that. Grizzly bears just take the top spot from gorillas in terms of my all time favourite experience, being in Alaska and off the beaten track and really removed from where I grew up in Africa, with animals that I hadn’t seen before, being in these raging Alaskan rivers with bears diving in in front of me and feeding on salmon was one of the most raw experiences I’ve had. I would encourage anyone to do it.

As and when we can travel more, where’s the first place you plan to visit?

I’m naturally very keen to get out and about, as I’m sure we all are having been locked up for so long. I try to look at my trips with a heavy photographic element, and part of me feels that I’d like to photograph orangutang in Borneo, it’s part of the world I’ve not been to before and the size of them, the colour of them - that deep orange, they’re such unique looking characters and I think photographically that would be an amazing trip.

Tigers in India is another, that would be incredible to get some great images of them. So those two are up there in terms of trips and obviously I’m hoping to get to Amboseli with you, Will. I think seeing some of those massive tuskers in such an open area with Mt. Kilimanjaro as a backdrop the context and the vastness of it would be an amazing experience.

As you now pursue photography full time, is there anything you are particularly focussing on?

Very much so, I’m now looking at increasing my corporate portfolio, working on a variety of commissions and assignments. I’m placing a lot of emphasis on my portraiture work as well, something I’ve really loved for the last few years and it’s something I’d love to do a little more commercially. I’ve got some exciting things coming up which can be followed on my Instagram here or over on my website.